Pang Tao (B. 1934)

Biography

Born in 1934 in Shanghai, Pang Tao began to study painting with her artist parents during her childhood. While her surname from her father is “Pang” (厐), her given name, “Tao” (壔), is a rare Chinese character that incorporates the part that means “earth” from her mother’s given name. For a large part of her life, Pang Tao went by the simplified version of her name, which contains less strokes but still sounds the same; however, towards her later years, she has gone back to using her name’s original form. The artist’s father, Pang Xunqin, was an important founder of the artistic system in the new China. He studied modern art in Paris in the 1920s and initiated the Storm Society (Jue Lan She), a modern art group, with fellow artists in 1931. He was also involved in the founding of the Central Academy of Arts and Design in 1956, where he served as vice president. Pang Tao’s mother, Qiu Di, returned to Shanghai in 1930 after studying oil painting in Tokyo, and she won an award in an exhibition organized by the Storm Society before joining the group. Before 1949, Pang Tao’s parents had been involved in the secret activities that led to Shanghai’s liberation. After the founding of the new China, Qiu Di worked at the Research Institute of Arts and Crafts from 1953 to 1957 as a fashion designer, while continuing to paint and design houses on sheets of paper. Throughout the war, the young Pang Tao led an itinerant life with her family in southern China, but she was already a budding artist. At the age of four, while in Kunming, she won third prize in the National Children’s Painting Competition in 1938. In 1948 and 1949, her parents held exhibitions for her and her younger brother, Pang Jun, in Guangzhou and Shanghai, respectively. In 1949, Pang Tao enrolled at the Hangzhou National Arts Academy (now China Academy of Art).

In 1951, Pang Tao retook and passed the entrance examination for the Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), and she transferred into the painting department’s Class A. At the time, CAFA did not have an independent oil painting department, so students learned all varieties of painting styles. The department had an extraordinary faculty during Pang’s time there. Oil painting instructors included Xu Beihong, Wu Zuoren, Ai Zhongxin, Dong Xiwen, and Xiao Shufang; printmaking teachers included Gu Yuan, Yan Han, and Huang Yongyu; and traditional Chinese painting instructors included Qi Baishi, Li Keran, Li Kuchan, and Liu Lingcang, among many others. Each teacher was an outstanding artist with a distinct personal style, yet they still predominantly taught the realist method during the basic trainings at the academy. Pang Tao was not interested in this type of instruction, but she had to follow it nonetheless. In September 1953, she began her graduate studies in the painting department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where she majored in watercolour.

Upon her graduation in 1955, Pang Tao was offered a teaching position in the printmaking department. During this early period, she created a range of bright grey paintings with realist features. Besides performing her teaching duties, Pang also went to Yunnan to paint illustrations included in textbooks for ethnic groups, which exposed her to the distinct landscape and topography of the area as well as the customs of local ethnic groups. The materials she accrued during the process enabled her to complete a series of watercolour paintings en plein air that focused on the verdure of southern China and ethnic cultures. These works distinguished themselves from the prevailing realist paradigms of the time with their bright, lucid colouring; steady strokes; and a spirited, breezy air. On returning from Yunnan,

Pang Tao started to explore ways of changing her artistic style. She created a few drafts with an abstract tinge, but the enterprise was soon interrupted by the sudden start of the Anti-Rightist Campaign.

In 1959, Pang Tao married Lin Gang, an artist who a year later would graduate and return from Ilya Repin Leningrad Institute for Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. She gave birth to Lin Yan, their daughter, in 1961. In 1965, Pang Tao was involved in the creation of a mural as part of China’s aid efforts for Guinea. Her draft was selected, but she was banned from the project the moment the Cultural Revolution began. This painting of hers was ultimately enlarged, created, and sent to Guinea after incorporating many “red, bright, and shining” elements typical of the time. From 1970 to 1973, she was forced to go to rural areas and paint posters. In 1975, a teaching team was set up at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. As part of the team, Pang Tao went to Dalian Shipyard and Dazhai Village for “open-door education”. Her job was to run painting classes for rural workers and children, as well as to perform propaganda duties. In her spare time, she also created landscapes en plein air and sketches of everyday life.

Between 1975 and 1978, Pang Tao took part in many artistic collaborations. In 1975, commissioned by People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, she collaborated with Zhan Jianjun to create a series of illustrated storybooks called Obstinate Girl, which features a girl from Inner Mongolia who fights fearlessly and cleverly against Nationalist Party secret agents. She then collaborated with Lin Gang and others to create several paintings on the revolutionary history including Premier Zhou, Our Closest Friend and Crossing East in 1976, Endless Poem on the Long March in 1977, and Eventful Years in 1978. While collaborating, Pang Tao usually took care of the sketches of the colour patterns, while Lin Gang worked on the structural compositions, but there were some exceptions. When they composed Endless Poem on the Long March, Pang Tao also created a draft based on the materials she gathered. The final version of the painting was based on her draft.

In February 1979, Pang Tao participated in the New Spring Exhibition at Hua Fang Zhai in Beijing’s Zhongshan Park. It was the first landscape and still life painting exhibition independently organized by artists after the Cultural Revolution. After its opening, several artists involved in the exhibition initiated and founded the Beijing Oil Painting Society. The society, of which Pang Tao is a member, reinstated the “letting a hundred flowers bloom” policy of the “first seventeen years” before the Cultural Revolution. Under the banner of “beauty”, the society also prized diversity in art and freedom of individual creation, encouraging individual explorations of artistic form.

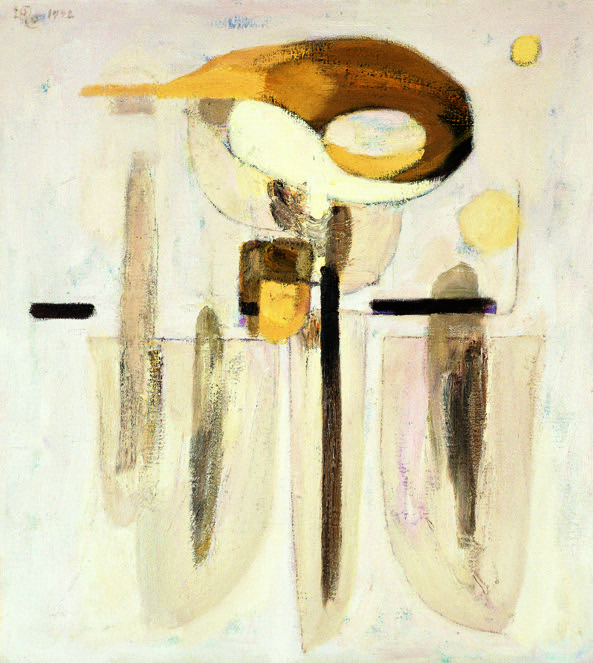

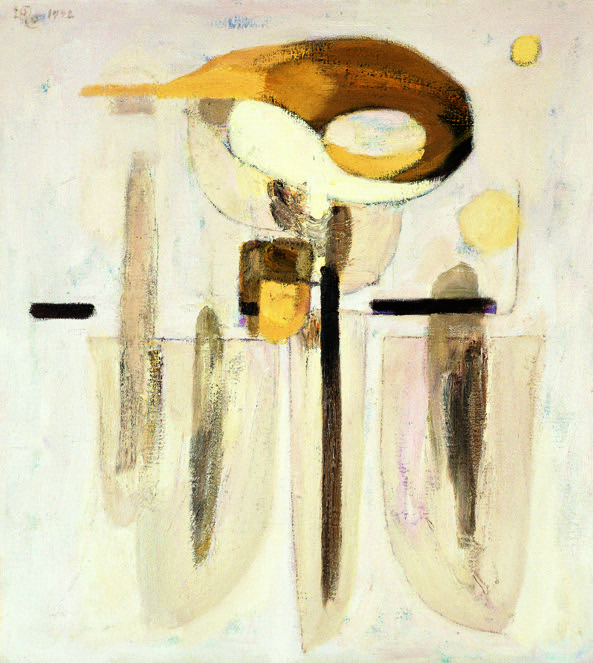

In 1980, Pang Tao started to experiment with sand as a medium for oil paintings. Her en plein air paintings produced during her excursion to Guilin with Lin Gang in 1981 demonstrate a remarkable shift in her style. Although she still adopted traditional, descriptive methods, Pang also began to develop an abstract style in these paintings. Part of this series also used sand as a medium. These explorations came into fruition in the new series Travels in Lijiang and Travels in Guilin, with the latter included in the Sixth National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1984. The work was divided evenly by design: a mountain was placed in the middle of the scene, resulting in the symmetry of both the mountain and the painting. The water and distant mountains are both blocks of colour, creating a decorative effect. The work attracted critical attention because it challenged familiar formal composition rules.

In 1984, Pang Tao lived in Paris for a year, as she was among the first group of artists that the government sent to Europe to study art. She carefully studied the art collections in galleries and museums in Paris and all across Europe, and she was deeply enriched by what she saw. Pang was exposed to ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Assyrian art; the Renaissance; nineteenth-century art; impressionist and modern art; contemporary art; African and Mayan art; Indian and other Asian art; as well as traditional Chinese art that had travelled to Europe. In the meantime, she closely observed and studied in a skills studio at the École nationale superieure des beaux-arts. The experience awakened her to the knowledge that the study and production of pigments and materials were by no means purely technical but were also integral to a serious, scientific approach towards the undertaking of artistic creation.

The year in Paris inspired Pang Tao to produce and publish Research on Painting Materials, her book designed for teaching. She was acutely aware of the fact that artists, beleaguered by the lack of choice of painting materials and their shabby quality, found it difficult to create freely in the new era of art. Therefore, she started experimenting with new and innovative materials for painting as a sideline to her own artistic creations, and she provided an extensive summary of the formulae and how-tos of numerous Western painting materials. Meanwhile, Pang was actively involved in teaching at Studio No. 4 in the painting department at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which was set up in 1985. The studio focused on modern art education and encouraged the free exploration of forms. Lin Gang was its director, and Pang Tao officially joined the studio in 1988.

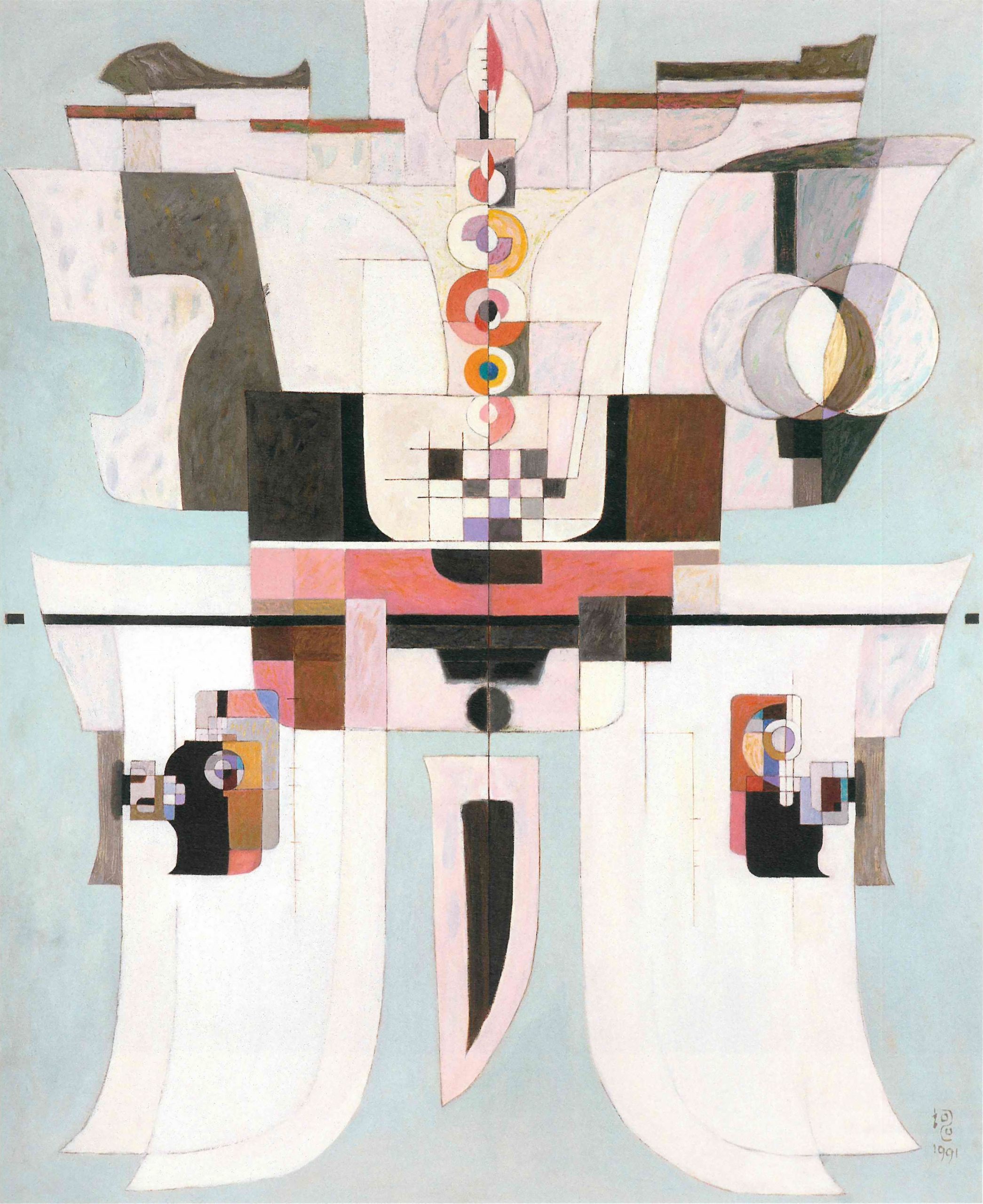

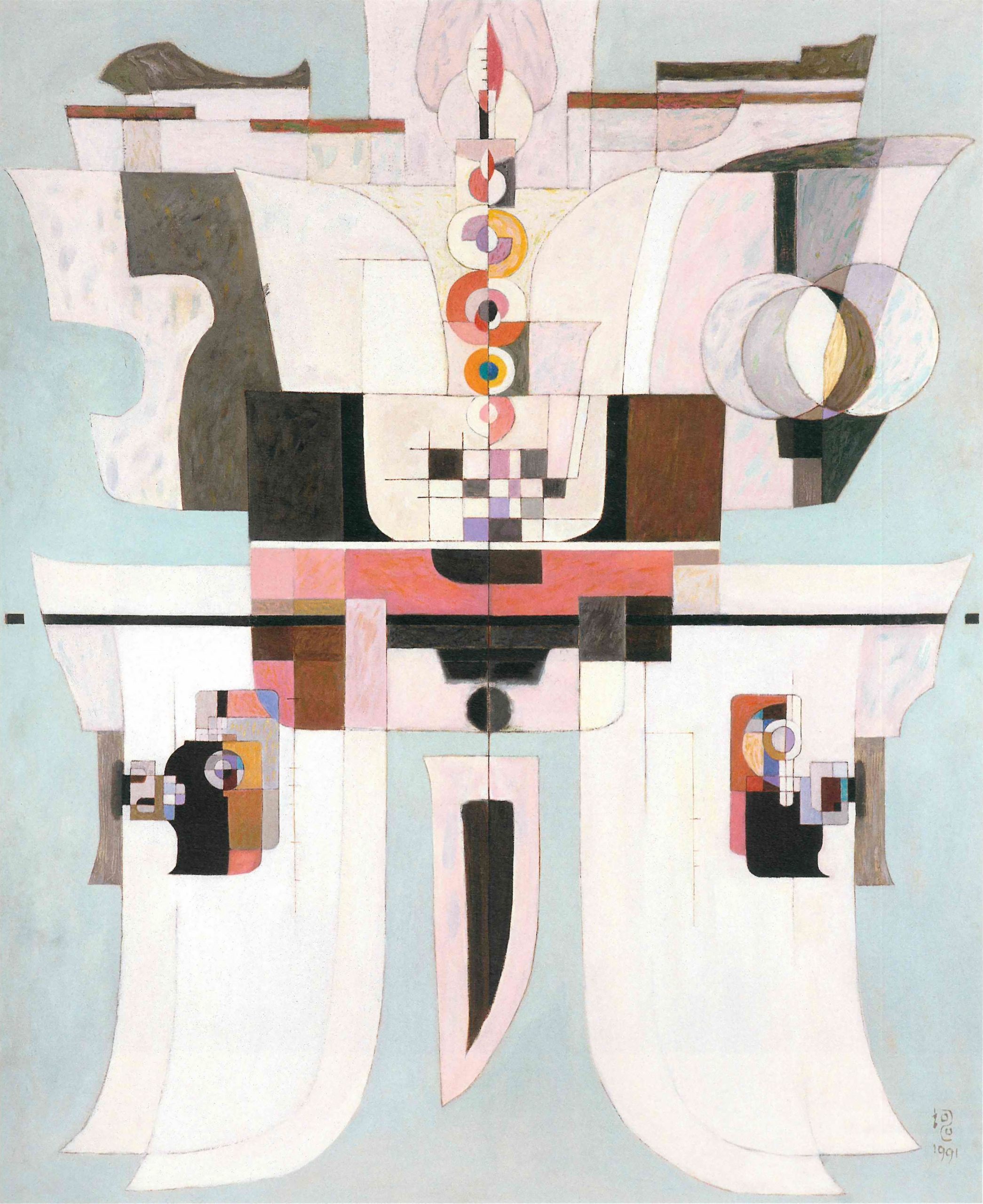

With regard to her own artistic practice, Pang Tao began to create a series of paintings featuring bronze ware in the 1980s. Her father’s death during her time in Paris was a heavy blow, but also animated her thoughts about integrating Chinese cultural symbols into contemporary art production and revisiting the rich resources of traditional Chinese patterns from the perspective of a formal language. The following decade saw Pang Tao use bronze as her subject matter. She applied a series of techniques including colouration, generalization, and the flattening of shapes. Such experiments persisted into the mid and late 1990s.

Pang Tao reached middle age in the 1980s, but it was also a decade when she embraced the prime time of her artistic creation. She found herself in a more relaxed society where there were less constraints regarding subject matter and from the social environment. Formal innovations quietly initiated by middle-aged artists like Pang Tao did not spark much critical discussion during the period of “chaotic artistic reforms” in the mid-1980s. The contrived categorization of art as “new” or “traditional” was often responsible for arbitrary disconnection and misunderstanding. Formal explorations and individualized expressions of art within art academies were consigned by young artists to the dusty archives and labelled as examples of “aestheticism”, “academism”, “traditionalism” or “conservativism”. Admittedly, some artists from academies actually had such tendencies; however, Pang Tao’s individual practices were neglected precisely because such general accusations, aimed at a wide spectrum of artists within institutions, obscured the truth.

Pang Tao retired from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1989. She then visited the United States and stayed for a year. On returning to China, she produced a series of collages, which was a continuation of her previous experiments on combining different media. Since 2000, Pang Tao’s abstract art has paid closer attention to social reality and has displayed deeper reflections on humanity. She created works related to the September 11 attacks and the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Now in her eighties, Pang Tao still demonstrates remarkable artistic vitality and continues to produce new works.